Source /www.newyorker.com The biography ( 4 docufilm) of Keith Moon and his technique explained by John Entwistle and other rock stars. Plus My life as Keith Moon.By James Wood.

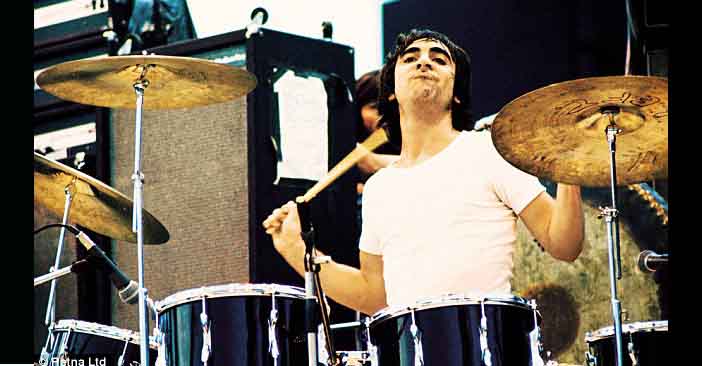

He was the drums not because he was the most technically accomplished of drummers but because his joyous, semaphoring lunacy suggested a man possessed by the antic sp irit of drumming. He was pure, irresponsible, restless childishness. At the end of early Who concerts, as Pete Townshend smashed his guitar, Moon would kick his drums and stand on them and hurl them around the stage, and this seems a logical extension not only of the basic premise of drumming, which is to hit things, but of Moon’s drumming, which was to hit things exuberantly. “For Christ’s sake, play quieter,” the manager of a club once told Moon. To which Moon replied, “I can’t play quiet, I’m a rock drummer.”

irit of drumming. He was pure, irresponsible, restless childishness. At the end of early Who concerts, as Pete Townshend smashed his guitar, Moon would kick his drums and stand on them and hurl them around the stage, and this seems a logical extension not only of the basic premise of drumming, which is to hit things, but of Moon’s drumming, which was to hit things exuberantly. “For Christ’s sake, play quieter,” the manager of a club once told Moon. To which Moon replied, “I can’t play quiet, I’m a rock drummer.”

2

Most rock drummers, even very good and inventive ones, are timekeepers. There is a space for a fill or a roll at the end of a musical phrase, but the beat has primacy over the curlicues. In a regular 4/4 bar.

Keith Moon ripped all this up. There is no time-out in his drumming, because there is no time-in. It is all fun stuff. The first principle of Moon’s drumming was that drummers do not exist to keep the beat. He did keep the beat, and very well, but he did it by every method except the traditional one. Drumming is repetition, as is rock music generally, and Moon clearly found repetition dull. So he played the drums like no one else—and not even like himself. No two bars of Moon’s playing ever sound the same; he is in revolt against consistency. Everyone else in the band gets to improvise, so why should the drummer be nothing more than a condemned metronome? He saw himself as a soloist playing with an ensemble of other soloists. It follows from this that the drummer will be playing a line of music, just as, say, the guitarist does, with undulations and crescendos and leaps. It further follows that the snare drum and the bass drum, traditionally the ball-and-chain of rhythmic imprisonment, are no more interesting than any of the other drums in the kit; and that you will need lots of those other drums. By the mid-nineteen-seventies, when Moon’s kit was “the biggest in the world,” he had two bass drums and at least twelve tomtoms, arrayed in stacks like squadrons of spotlights; he looked like a cheerful boy who had built elaborate fortifications for the sole purpose of destroying them. But he needed all those drums, as a flute needs all its stops or a harp its strings, so that his tremendous bubbling cascades, his liquid journeys, could be voiced: he needed not to run out of drums as he ran around them.

Keith Moon-style drumming is a lucky combination of the artful and the artless. To begin at the beginning: his drums always sounded good. He hit them nice and hard, and tuned the bigger tomtoms low. (Not for him the little eunuch toms of Kenney Jones, who palely succeeded Moon in The Who, after his death.) He kept his snare pretty “dry.” This isn’t a small thing. The three-piece jazz combo at your local hotel ballroom almost certainly features a “drummer” whose sticks are used so lightly that they barely embarrass the skins, and whose wet, buzzy snare sounds like a repeated sneeze. A good dry snare, properly struck, is a bark, a crack, a report. How a drummer hits the snare, and how it sounds, can determine a band’s entire dynamic. Groups like Supertramp and the Eagles seem soft, in large part, because the snare is so drippy and mildly used (and not just because elves are apparently squeezing the singers’ testicles).

in 1968, Jimmy Page wanted John Entwistle on bass and Keith Moon on drums when he formed Led Zeppelin; and, as sensational as this group might have been, it would not have sounded either like Led Zeppelin or like The Who.

The third great Moon principle, of packing as much as possible into a single bar of music, produces the extraordinary variety of his playing. He seems to be hungrily reaching for everything at once. Take, for instance, the bass drum and the cymbal. Generally speaking, drummers strike these with respectable monotony. You hit the crash cymbal at the end of a fill, as a flourish, but also as a kind of announcement that time-out has, boringly enough, ended, and that the beat must go back to work. Moon does something strange with both instruments. He tends to “ride” his bass drum: he keeps his foot hovering over the bass-drum pedal as a nervous driver might keep a foot on the brake, and strikes the drum often, sometimes continuously, throughout a bar.