When Brian Wilson first heard the Beatles’ 1965 album Rubber Soul, he was so astonished by the album that the next morning, he went straight to his piano and started writing “God Only Knows” with his songwriting partner Tony Asher.(Medium.com)

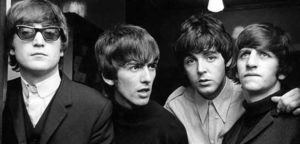

Wilson knew that Rubber Soul — an album that contained the most mature songwriting from John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison yet, and exhibited the beginnings of a studio effects revolution — was a glimpse into the future of rock music, and that the Beatles were at the forefront. As cofounder of the Beach Boys, he knew that music was changing and for his group to stay on top in the industry, he would have to make something just as good, or better.

The result was Pet Sounds, released May 16, 1966. It was the Beach Boys’ greatest artistic achievement; one that would never be reached by the group again.

But for the Beatles, 1966 would prove to be just the beginning of an explosion of artistic and technological innovation that would not just change the group, but would alter rock music forever. Revolver — which turns 50 this month — was the culmination of that innovation. And it almost didn’t happen.

1966 was meant to be much like the previous two years for the Beatles. Mapped out by manager Brian Epstein, the group would shoot a film, write and record a soundtrack for that film, tour, and then record another album. But when the Beatles couldn’t agree with Epstein on a movie script, the film project was scrapped. This gave the group some unexpected free time. And what better way to spend that time than in the studio?

Because the Beatles were now so established in the industry, the group felt they could take more risks when it came to the type of songs they produced. And the extra time off allowed them to explore ideas they might not otherwise have gotten to had they been under such a tight schedule.

It was during this time that the group fully realized just how much touring was having an effect on them. Live appearances had provided them with the bulk of the money they were earning. But touring also limited the band to the music they could play — mostly songs that could be easily reproduced on stage. But as Rubber Soul proved, the Beatles’ music was becoming more complex, not just from a lyrical perspective, but also from a studio engineering standpoint.

As Robert Rodriguez points out in his book, Revolver: How the Beatles Reimagined Rock ’N’ Roll:

“The situation demonstrated the dichotomy between fulfilling duties out of financial need (and fan demand), and pursuing their artistic destiny in the studio, where their creative heart lie. As far as they were concerned, the latter course was the way of the future.”

But it wasn’t just the Beatles who were changing; it was the fans, too. As hard as Brian Epstein tried to maintain the band’s innocent, lovable mop-top image, controversies surrounding the group abounded. First, John Lennon’s infamous remarks to journalist friend Maureen Cleave about the Beatles being, “…more popular than Jesus now” caused an international uproar among many Christians.

Capitol Records sent 60,000 copies of what is now known as the “butcher cover” album, Yesterday and Today,to stores and the media weeks before its June 15 release, only to be pulled and replaced with a much safer, albeit boring, cover a very short time later. And then, during the Asian leg of their 1966 tour (which would be their last), two separate incidents — one involving First Lady Imelda Marcos of the Philippines and the other in Tokyo, Japan, involving the Nippon Budokan — a venue meant for martial arts, not so much rock concerts, according to some locals.

To fans, the Beatles, had become fallible for the first time in the group’s career. And reporters — who seized every opportunity to exploit the band’s time of weakness — ate it up. Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Ringo Starr found, more than ever, comfort and solace in the studio, where the makings of Revolver began taking shape.

But the touring, fan controversies, and insatiable media weren’t the only factors that led the Beatles to crave more creative time in the studio. It was what was going on in their personal lives as well.

Harrison continued his education of the sitar under the tutelage of mentor Ravi Shankar, as well as with transcendental meditation. McCartney began exploring the London art scene with his then-girlfriend Jane Asher, delving into theater, classical music and other high-brow culture. John Lennon took up acting, starring in How I Won the War in Germany. He also met experimental artist Yoko Ono at the Indica Gallery.

And then there were the drugs.

In 1966, the Beatles weren’t new to the concept of drugs. Their shows in Hamburg in the early 1960s were fueled by the appetite stimulant Preludin, which gave them what seemed like unlimited energy to play for hours, until it wore off. And then they’d simply pop more. If Rubber Soul was known as the pot album, then Revolver would be known as the LSD album.

In 1966, the Beatles weren’t new to the concept of drugs. Their shows in Hamburg in the early 1960s were fueled by the appetite stimulant Preludin, which gave them what seemed like unlimited energy to play for hours, until it wore off. And then they’d simply pop more. If Rubber Soul was known as the pot album, then Revolver would be known as the LSD album.It would be foolish to attribute the innovative surge the group experienced during the Revolver sessions to LSD alone, but it certainly didn’t hurt when it came to opening up their minds to musical possibilities that might not have been seen otherwise.

Although Rubber Soul had hinted at new directions in the Beatles’ music, it was the group’s June 1966 release of the single “Paperback Writer” that drove it home. Its b-side track “Rain” tinkered with backwards vocals, experimental bass effects and new technologies at Abbey Road Studios.

To achieve all that they did in 1966, they couldn’t have done it without a little help from their friends—in this case, some friendly competition from other artists in the music scene at the time. Bob Dylan’s landmark album Blonde on Blonde was released, which included, arguably, two of his greatest songs — “Visions of Johanna” and “Just Like a Woman.” The Rolling Stones’ also released Aftermath, which consisted — for the first time in the band’s history — songs all written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. It also included a variety of instruments not usually associated with rock albums, including marimbas, the Japanese koto and the dulcimer.

They also benefitted from friends in the studio. Most notably, producer George Martin, who by all accounts, was the closest thing there was to a “fifth Beatle.” Martin helped guide the group’s innovative sound— from the double-string quartet on “Eleanor Rigby” to the French horn obligato on “For No One.”

But it was also thanks to 20-year-old engineer Geoff Emerick, who was promoted to replace veteran Norman Smith. Emerick is most notable for his work on the first track recording for Revolver, Lennon’s “Tomorrow Never Knows.” By recording his voice through a Leslie speaker, it gave it the faraway sound the song is known for, which was something that had never been done before. It was ideas like this, along with the microphone placement for McCartney’s bass and Starr’s drums, that paved the way for the way studio recordings were done after Revolver.

But it wasn’t just the studio effects and instruments that made Revolver stand out from the rest of the Beatles catalog. It was the songwriting.

All four Beatles were arguably at their artistic peak in 1966. But during the Revolver sessions, the group also showed signs of crumbling as each member started pursuing their own creative paths.

In August, the Beatles performed their last live show of their final tour, at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. And as 1966 neared its end, the group began work on “Strawberry Fields Forever,” a song written by Lennon that would guide the band’s musical direction in the coming year.

In 1967, when Brian Wilson first heard the song, he pulled over in his car, broke down in tears and said, ‘They got there first.” Then, later that year, after hearing the Beatles’ next album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, he had a nervous breakdown.